Meditations on Lunch, a Word in English and Peruvian Spanish

English words, like strange ghosts, often appear in the midst of Spanish sentences in Cuzco. Some of them, like “men”, or “brother” are stylish and of the moment. Others seem to have been there for a long time and, like ghosts, have stories, sometimes hidden ones. The word lunch is one of these last ones. It has been around long enough to adapt to its new surrounding, yet not long enough to lose its English touch.

In Peru they pronounce it lonche (lóan-cheh). When I first heard it, my mind trained during a childhood on the US Mexican border in the embrace of Spanglish heard it as identical to its sibling in English. After all, in my El Paso, “lonche” was simply one of the ways you could say “lunch” while also signaling your position in the city’s class, ethnic, and linguistic divides. While the pronunciation would change, the meaning seemed to stay the same.

It meant the midday meal. Whether what us school children would carry in paper bags or colorful, light metal boxes or simply what one ate to get energy and nourishment while dividing the day in two, whether at noon or two pm.

But the Peruvian lonche was a flirt with different intentions and meanings. In the Peruvian Andes this widespread word seems to replace what in Victorian England was “tea”, a hot drink and something with it eaten around five in the afternoon.

In nearby Bolivia, this time slot starts a little earlier, around 4 pm, and is simply called “té”, that is tea.

And that is what it is, a late afternoon pick-me-up and social occasion. One can only imagine that the Victorians, who replaced the Spanish as the dominant power of the Pacific, pushed the railroad up mountain, and introduced foods and sport alongside their economic might, all of which haunts ordinary usage today. Words such as fútbol, football, gasfitero, gassfitter or plummer, smoking, or tuxedo, and of course lonche, flitter around Peruvian Spanish.

Some like the sport are found throughout Latin America while others make Peruvian Spanish stand out as unique. It has its own set of English origin words, just as it has a national soda–Inca Kola– developed by an Englishman.

However, without doing the detailed work of history, one can only imagine this. But like ghosts these words require a reading, a telling, a work of the imagination.

As a result, other intriguing questions arise like spooks.

Why does this obviously Anglo import–which now testifies to a process of going native like Peruvians with the last names of Bayley, Bryce, and Peel, among many others from Avalon–now have such a different meaning from its US English cognate? Instead of a midday meal it speaks to a snack in the late afternoon.

The popular Peruvian writer, Martha Hildebrand argues this is because the word lunch in English meant a light meal. When I read this my Anglo hackles raised. A lunch does not have to be light, it just has to be in the middle of the day. I thought of all the relatively heavy meals served then, as well as the many times we just grab a sandwich. The size of the meals is just not important to the current definition.

So I looked to see the history of meaning of the English word. Hildebrand is right, darnit. Evidently the word comes from luncheon and did mean a light meal or snack, although it tended to be eaten in the north between a heavy breakfast and a large evening meal. (Even stranger, some scholars think the word originated with the Spanish word lonjas, or thin slices, of something like meat. This just gets weird. A word I know as stereotypically English, may have originally come from Spanish, and has now returned to Spanish where it coexists with its genitrex? Language is so strange!)

In Peru, if HIldebrand is correct, then the word focused on the smallness of the lunch and connected it with English tea, not the drink but the time and meal.

So I looked up meal times. It looks like both lunch and tea are products of the Industrial revolution that with new work regimes not only removed people from the land and disciplined them, but also gave them new times of eating and new styles of food, such as sandwiches and tea. The idea of tea time seems to have developed in England around the time Bolivar and San Martin came from the north and south to slice Peru from the Spanish body.

As a result, Peruvians needed new words for new things, like the time of taking tea, and of eating a light meal, since they continued with their inherited, Mediterranean custom of a heavy meal eaten in the early afternoon.

So the word lunch, reformed with a Spanish pronunciation, seems to have become the word for this new, mercantile, capitalist, minimalist meal and time.

But tea came as a bourgeois custom, one of the British bosses. How did it become generalized into the lives of ordinary Peruvians and present throughout urban Peru at least?

To explain that, I think, we will have to rely–in the absence of long research in the archives–on the idea that lonche must have spread with the urbanization of the country, the development of a mass society, and the strong growth of patriotism and nationalism all in the twentieth century.

For example, there is even a popular radio program called the hour of lonchesito, that is an endearing lonche, from Radio Felicidad to entertain people around five pm. It plays romantic and nostalgic songs “of memory”. As a result, a researcher would want to look at the role of radio and programs like this, as well as of other mass media, in creating this part of national culinary culture.

But there is more. In Cuzco, a lonche can be at any time five pm or so and after. It refers to the hot drink people consume then, as the sun sets and the cold of night starts, along with something else.

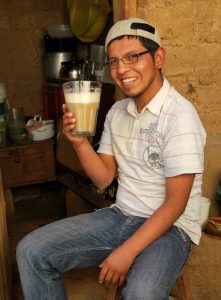

The drinks can be a coffee, a hot chocolate, a tea, or one of the ponches (hot ground toasted bean or nut drinks) of Cuzco. The rest can include any of Cuzco’s breads of pastries, in addition to a tamale, an huminta, a savory or sweet empanada, or a small meal, such as one of leftovers from the mid-day repast.

In Cuzco the lonche becomes Andean again. And, it also runs up against the custom of going to a chicheria at this time for a glass of the fermented corn beverage and sometimes a small uchu, or picante, a modest dish of some savory concoction. These two, the chichería and the lonche are distinctly not the same, even if they occupy the same time frame.

That meeting of the English lunch and the Quechua chicha, however, will have to be a meditative task for another day.