Masks, Satire, and the Sacred in Cuzco

Dance is an important part of traditional Cuzco life. Whether in the cities with their folk festivals and their feasts celebrating a patron saint or in rural communities from high Espinar Province to the lowland La Convencion, dance plays an important role. As part of dance, participants generally wear costumes which often include masks.

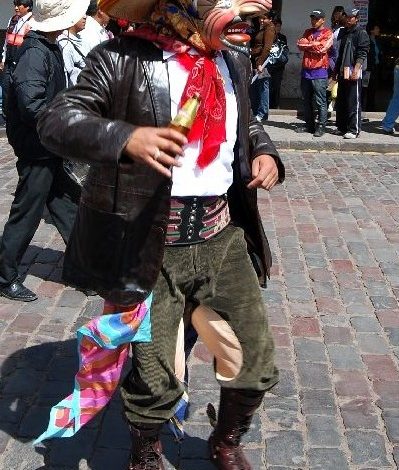

You can stand in the plaza in Cuzco and watch ukukus dance by with their white woven masks and high pitched, falsetto voices. Or you can see majeños dance by with their long nosed masks in place.

The result is stunning and draws large crowds of tourists as well as people from Cuzco to watch the dancers go by.

If you ask, or look on line, there is often a story to go with the dances and their masks. Commonly people will say that the dances “satirize” something or another. But this word, “satirize” means one thing to me and probably another thing in the history of Cuzqueño dance.

To me the word satire refers to heightening something as a means of making it ridiculous and, as a result, attempting to gain a certain power over it. Satire is a high art.

But in the dances, I think, the word draws on an older tradition from Europe that blended with Andean ways giving us, with many years of history in between, contemporary dance in Cuzco.

As a means of getting at this tradition we can notice that Garcilaso Inca de la Vega, in his Royal Commentaries, refers frequently to dance which he almost always joins with song. He describes these two as “solemnizing” an event, or for us “making the event sacred.”

Garcilaso suggests to us, in the way he uses language, that dance with song somehow made events different and brought to them a significance far beyond the ordinary. They became focused, intense, and sacred, as a result.

This word “sacred” seems to refer to God or the supernatural as what makes something holy, but it can also be made by being set off from the ordinary by something like dance and music.

Here is where the word “satire” becomes meaningful. An Italian dictionary of etymology (the origin of words) notes that satire was “in its origin [. . .] a kind of drama, in which were mixed music, words, and dance or, as other indicate, poetry.” For the Spanish it is likely the dances of the Inca and their descendants were called “satire” to distinguish them from the rituals of the Church which were “sacred” by definition. The heightening typical of ritual was common in both the one and the other. The only difference was that satire increasingly became seen as a form that uses irony and makes ridiculous or funny, almost the opposite of what holy and serious ritual should be.

Of course clowns, such as the ukuku, were always part of Andean ritual. To make more sense of this, let us look more closely at the masks such as those the ukuku wear.

Instead of humor or stereotyping someone in ways that subjected them to dismissal or stigma, they could instead exalt them.

The Huarochiri collection of stories suggests something like this.

They tell of the “huaca” (we could say “holy figure like a saint” so as not to run afoul of Garcilaso’s correcting the Spaniards when he wrote that the word huaca does not always mean god and may simply refer to things that are unique or set apart, such as heroes or significant places) Ñan Sapa, which in Quechua means the “path that is single or unique”.

They say he used to be a human being and wore a special gauge in his ear and carried an important staff, spear, or scepter in his hands. The people of Vichi Cancha said that he was their beginning. “It was he who first came to this village and took charge of it”, they said.

The story then says that the villagers removed his face and made a mask of it. Not only did the mask carry the being of Ñan Sapa, the Holy Way, it also kept him alive, especially when “they made the mask dance as if in his own persona”.

The storyteller then pauses to note that the people of Vichi Cancha would also make masks from the faces of men captured in warfare. Before they could kill him and make a mask of his face they would have to give him good food and drink in abundance.

When they fed him they would also say “this day you shall dance with me on the plaza”.

As a result, people would bring the masks out with great care into the plaza, offer them food and drink, and have them participate in the feasts and dances. Then they would be hung up with “maize, potatoes, and other offerings.”

People would say that the masks “will return to the place where they are born, the place called uray pacha (the land below) carrying these things along with them.”

The story also indicates that when talking, those wearing the mask, would “speak with a different pronunciation [ . . . ] twisting their mouths to the side.” In a footnote, the editors and translators of the Huarochiri tales, Frank Salomon and George Urioste, tell how even today people like the ukukus speak differently, they speak in falsetto. They also say the words could mean that they twist their language to say something different than what is plainly meant.

The ukukus will often do this as well, though the scholars do not note that. They will use misstatement and teasing to engage spectators as part of a holy satire while saying that which is not said in polite society, or even saying things that are wrong.

If we follow along with the Huarochiri tales then we can argue that when Garcilaso says dance and music “solemnize” they do so because of three things:

- they stem from origins or recognize mighty figures, including enemies;

- they are not the ordinary and do not speak in ordinary ways;

- they have to do with fertility, of people, animals, and crops which is why it is important to note they return to the beginnings, to Uray Pacha, with gifts to encourage children, baby animals, and baby plants to keep coming to living people.

When we see an ukuku with his white knitted mask, or a majeño with his big nosed mask we are seeing the faces of captured beings, whether Andean bears or Spaniards. They do retell pieces of a history–as the contemporary stories accompanying dances relate, but they also carry the holiness of relating to origins and creating fertility at the same time they create sacred satire.

The Spanish may have tried to contain this by limiting feasts and by seeing it as satire in contrast to the Church’s sacred, but they allowed it to continue and today, even when performed as folklore, it carries in it this earlier meaning of making an event sacred and of presenting how people and their world originate and are reborn as life continues onward.

Reference: Chapter 24, Frank Salomon and George Urioste, The Huarochiri Manuscript: A testament of Ancient and Colonial Andean Religion (The University of Texas Press, 1991) pp 120-121.