Cuzco’s “Cooking with Irma” Concentrates Time and Place

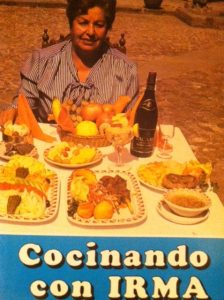

What do mayonnaise, guinea pig pipián, stuffed pot roast in a Coca Cola sauce, spinach filled raviolis, and chiffon cake have in common? They are all found in a classic cook book from Cuzco, Cocinando con Irma or Cooking with Irma. Written by Mrs. Irma Aquise Bocángel de Muñiz it has gone through various editions and remains a classic in the Peruvian repertoire and especially in its Cuzco variant.

With its several editions (I know of at least three) each a little different, the book has continued to have life at the same time it represents a time and a place.

Cook books are like that. They are concentrations, just like a good broth which brings the ingredients together in ways that represent only that moment’s sum of the parts. Every generation that finds authors wanting to collect recipes and publish their books is different than any other generation.

Food has its own existence and it is not that of the cookbooks, unless we wish to confuse Google Maps for a trip around the world, or a video chat on Skype for being in a cafe with someone, sipping a good coffee and conversing.

While I have not met Doña Irma and decided to write this piece while far from Cuzco and its resources, one can see a lot just by looking at the book. Writing about food today in Peru is driven by the current push to brand and develop Peruvian gastronomy as part of a campaign for international recognition and internal development.

In this way a dish, say ceviche–now definitively spelled cebiche–becomes so much more than good, fresh-caught fish lightly marinated in Peruvian lime juice. It now stands in the light of press campaigns, specialists, and culinary institutes, as well as fine restaurants.

No longer is it simply something that is made in the home for a family meal or something one eats in a cevichería on the coast.

It is now a symbol of Peru, seasoned with the press and restaurant savoir faire of a larger than life Gastón Acurio, and much needed for professional gastronomy to develop and claim its place at the center of Peruvian life.

Doña Irma wrote long before this very contemporary creation of the Peruvian essence and its various versions, long before glossy cookbooks touting Peru competed for international awards.

Instead she made her recipes, tested them, and published them at a moment and for a particular audience.

Her’s was not the Cuzco public that today sees itself through imagined tourist eyes. Instead hers was a Cuzco at the cusp of rapid demographic growth. The region had been growing for decades and was approaching the peak in growth rates. The three way civil war had broken out among the Shining Path, the MRTA (Revolutionary Movement Túpac Amaru), and the Peruvian State. Though not as violent in Cuzco as in neighboring regions, the war nevertheless did shake society and fill it with excitement and dread.

In this moment, Doña Irma, a teacher at the well-known Educandas School for Young Ladies. This school has a long connection with the hopes and fears of Cuzco’s upwardly mobile middle class. And to the housewife building a life and place in society at that time the book seems directed.

It is a kind of Betty Crocker Cookbook, or a Good Housekeeping Cookbook. You know, the kind that was given as gifts to young women entering adulthood and to couples just getting married. In its pages are boiled down much of the wisdom of middle class life in Peru.

That seems how chiffon cake and mayonnaise got bound with stuffed pot roast, coca cola and a recipe for pipián.

International cuisine–the position of one as a member of an ascendant class, consumer consumption of things like gas stoves and refrigerators not to mention ketchup and Coke (which claimed that “things go better” when it is in the mix)–gets paired with creole cuisine–the definition of one as a member of a country and a people–and they join local cuisine, what Doña Irma calls “typical dishes” or membership in Cuzco.

While the first two one had to learn, either from travels or studies, the last one–Cuzco style cuisine–would have been learned from local people and tradition. But with the growth of the city and social mobility the traditional ways in wish recipes were passed from person to person shifted and people needed guidance of professionals. In this case the professional was a local Julia Childs, a teacher from the Educandas school whose students already knew and respected her.

Nevertheless, like those classic North American cookbooks for the person claiming middle or upper middle class status before a flood of cookbooks with diverse and changing refined tastes hit the market, Cocinando con Irma is still worth consulting and cooking from. Using it is more than simply making food, it is reviving a time and place, as well as a style and status.

While the North American cookbooks were envisioned for a national and international audience and so mark the formation of a large mass society, Cocinando con Irma was primarily for her Cuzco audience. Nevertheless it did attain a national audience as that mass of consumers developed.

Unlike the American cookbooks, which were the product of corporations looking for market share, Doña Irma is a real person and a cultural icon in her city. After all Betty Crocker is a commercial fiction. She never existed and was created for marketing purpose, even though she became real to generations of cooks in the United States.

The book can still be found in bookstores around Cuzco in its most recent edition as well as online and in major Latin America library collections in the United States.

Since pears are currently filling markets in the United States and other northern climes, here is Doña Irma’s recipe for a Cuzco-style Pear soup, a chupe de peras.

Chupe de Peras

Ingredients for 10 persons: 1 1/2 kilos of meat; 1 small piece of chalona (dried meat); 1 kilo of potatoes; 1 cup of popped wheat; 20 pears of normal size. For the rehogado: 1 cup of finely diced onions; 1 teaspoon garlic; 1 teaspoon pepper, salt as needed and oil.

References: You can also prepare the chupe de peras in a white broth of rice, add the boiled pears, this is in the Arequipa style.

Preparation: Place to boil the meat with carrots, onion, garlic, salt, and chalona, let it boil if you wish in a pressure cooker (three whistles–pitadas).

Strain the broth, prepare the rehogado with the onions, garlic, 1/2 cup oil and pepper, let it cook well.

Place in the pressure cooker, together with the meat broth, if it happened to still be tough, the chunked potatoes and the wheat, let it give a whistle, take it from the heat, and let the cooker cool.

Pour it over the rehogado, let it boil a bit to absorb the flavors better, before serving add a bundle of oregano, yerba buena (mint), and cilantro; serve by placing in each bowl two pears, previously stewed.

Note on translation

In the translation we have kept the style, format, and punctuation of Doña Irma’s text even though they do not correspond to proper contemporary style.