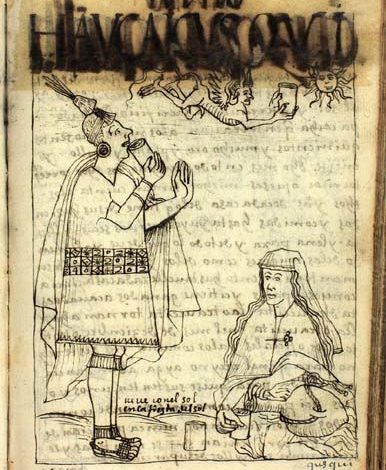

A Spanish View of Inca Food

The Inca presented many puzzles to the Spanish who invaded their land. Inca ways were not the same as European ways. And, the Europeans struggled to grasp them from the world of their own culture.

Bernabe Cobo wrote an important chronicle of the Inca in the seventeenth century, almost a century after they had disappeared. A Jesuit, he spent years in Peru, both upper and lower, and made use of exiting documents. As a result, his comments on Inca cuisine are both useful and intriguing.

In writing about their vegetables, I have already stated that the ordinary bread that they eat is maize, quinua, andchuño or dry, fresh papas (potatoes). Maize is toasted in clay casseroles pierced with holes, and it is their bread. It is the most usual ration of food that they take with them on their journeys, especially a maize flour that they make. They toast a certain type of maize until it bursts and opens up: they call it pisancalla, and they consider it a delicacy. There are small cakes and rolls ordinarily made from maize flour called tanta. Apart from them, as a treat, from this maize flour they customarily prepare some small cakes by cooking them in a pot. These cakes are called huminta.

It has already been stated what wines they have and how much these people are given to drinking. In ancient times they had few viands and stews. They made a certain kind of stew called motepasca from whole kernels of maize with some herbs and aji peppers. The maize was cooked until it split open. Another stew called pisqui was made from quinua seeds. These two stews correspond to the ones that we usually make with rice, garbanzos, and other similar things. The plebeians ate very little meat, and when they did it was at festivals and banquets. They ate more dried meat than fresh, and they prepared the dried meat without salt in the following way. They cut the meat in wide thin slices. Then they put those slices on ice to cure. Once the slices were dried out, they pounded them between two stones to make them thinner. They call this meat charqui. From it and from fresh meat, they only knew how to make one kind of stew called locro. It had a lot of aji peppers, chuño, papas and other vegetables. They made the same stew with dried fish, which they ate quite often. In short their cooking was so rustic and crude that there was nothing other than poor stew and worse roast over the coals because they never had roasting spits.

Though Cobo, no doubt for the benefit of his ethnocentric Spanish audience, found Inca cooking “crude”, a surprising amount of continuity exists between his narration and contemporary food in Cuzco and nearby areas. The techniques and dishes he describes are still eaten. The names are recognizable in their contemporary form and are very tasty, requiring skill in preparation. So, we shall end this post with a glossary of the ingredients and dishes; we plan to describe them individually in later posts.

Aji

Hot peppers in quechua as discussed here.

Charqui

Jerky, one of the few words that came into English from Quechua.

Chuño

Potatoes that are first frozen then thawed before the water is squeezed out of them and the process repeated. Once completely dry they can last a long time and continue to be a staple in the Andes, both in their black form for which the word chuño is used and for the white form called “moraya.”

Huminta

A cake or a tamale made of ground sweet corn.

Locro

A stew which today generally includes squash.

Mote

Similar to hominy, this is dried corn that is rehydrated and often served as a side to various meats.

Papa

Quechua for potato. This tuber originates in the Andes where they are innumerable varieties each with its own flavor and texture. The English word comes from an indigenous word from the Island of Hispaniola which became “batata”, originally for sweet potatoes. The Spaniards made it “patata”, the word still most commonly used in Spain, while South Americans prefer the Quechua word “papa”.

Pasca

A stew that contains mote.

Pisancalla

Large kernels of corn that are popped. Today they are still served. Near Lake Titicaca the name is still preserved as “pasankhalla”, although in Cuzco and much of Peru it is today called “maná”. Although sometimes served plain, it is often sweetened.

Pisqui

A nourishing gruel of ground quinoa, often served for breakfast with milk and cheese today in the area near Lake Titicaca.

Quinoa

A protein rich seed of the chenopodium family; it is increasingly found in supermarkets in Europe and the United States and is entering cuisine far beyond the Andes.

Tanta

Today this Quechua word is used for “bread”, although in the Cuzco dialect it is spelled “t’anta” in order to capture the explosive first letter in the way it is pronounced there.