The Myth of Inca Origins and Food

Food and myths have an intimate relationship, as we have become increasingly aware during our work on understanding the culinary culture of Cuzco. In this light we can explore the story of the founding of Inca Cuzco and the dynasty for what it can tell us about food.

When the Incas ruled Cuzco, they had many temples with priests, part of whose charge was to remember stories related to their shrine and to carry out appropriate rites. With the Spanish invasion, these temples were replaced with Catholic shrines, or simply destroyed over a period of time. The priest and their stories were often lost or remained in only fragmentary form.

As a consequence, most of the myths that governed life were lost, even if fragments remain in the names of mountains, the practices of dancing, and in the writings of the Spaniards who came to Peru in the sixteenth century and later and wrote about what they saw. Some of the stories can also be found in the writings of priests about the problems of Christianizing the Peruvians and of stamping out their native faith.

One Spaniard who wrote down some of the mythology, Juan de Betanzos was connected with the royal family through his wife, Doña Angelina, the former sister wife of the murdered Emperor Atahuallpa. As a result, many commentators argue he reproduced much of the vision held by his wife’s branch of the nobility.

His chronicle, entitled Suma y narración de los Incas (translated into English as Narrative of the Incas) begins with the story of the beginnings of people and civilization at Lake Titicaca, as well as a destruction and rebirth. Betanzos tells that people came from springs and caves all over the Andes. He then narrates one example of this in the origin of the Inca royal family.

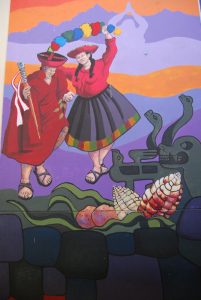

This myth, often called the story of the Ayar Brothers and Sisters, tells of the coming of four pairs of brothers and sisters from a cave called Pacarictambo, the place of production according to Betanzos, although a contemporary definition might be the Inn and Storehouse of Dawn.

From Pacarictambo, Betanzos narrates their journey to Cusco with adventures along the way that led to one brother being enclosed permanently in the cave of provisioning and another becoming a stone statue on an important hill near Cuzco called Guanacaure. The remaining two brothers and four sisters settled in Cuzco where the current Qori Cancha (Temple of Santo Domingo is) thanks to the permission of Alcaviza who already lived here with his people, and began the generation of Incas.

Although there are many ways of looking at myths, we cannot help but notice, given our interest in food, that the narrative easily divides into two parts which end with the planting of crops: first potatoes and then corn, the two major foods that are the historic basis of life in the Andes. Furthermore, Betanzos observes that the Incas brought the seed for these crops with them from the cave Pacarictambo.

While most discussion of this story emphasizes that it tells the founding of the Inca dynasty and their settlement in the city Cusco, it also narrates the origin of these two key foods. They become key elements of a political order related to providing food to people through a privileged connection with the earth and the sun.

Both of these stem from a mountain, from which they came forth with the four sets of Ayar siblings. As a result, it is not surprising that in Cuzco their is an aesthetic preference even today for piling up food carefully on the plate so that it resembles a large and imposing peak.

But there is more to this than simply mountains, potatoes, and corn. It is argued that the name Ayar refers to a kind of quinoa. Whatever the truth of this, it suggests that instead of simply being an Andean dualism of potatoes and corn, there is a third, a base on which the two were established, quinoa.

And, beyond this there are at least two more references to food. These rest in the names of two of the Ayar brothers. While there is debate about many of these names, there is not about these two. They are Ayar Cache and Ayar Oche, as Betanzos spells them.

Cache, generally spelled cachi today, is the Quechua word for salt. The story tells of the frightening strength of Ayar Cache, or the Ayar Salt. He could take his sling and toss stones with such vigor that they would break mountains and split them into deep canyons.

As a result, his other siblings were afraid of him and sent him back into the cave Pacarictambo to get the precious things they had left behind. Once inside they covered the cave mouth to not let him back out before walling it up. He remained trapped inside the mountain, although from there he could help is siblings outside.

If we look at this as an allegory about salt, we notice that salt is also very strong. It can form breaks in things by sitting on them. But when used in small amounts, salt makes food taste good, it transforms it. It can also make food last longer, stopping the process of rotting, as it does with chalona or salt dried meat.

Furthermore, salt comes from underground. Today, the most famous producer of salt in Cuzco is Maras where a salty stream flows down the hilll, through salt pans, depositing pink salt crystals that are widely treasured.

The other brother whose name easily relates to food is Ayar Uche, in Betanzos. Other authors list him as Ayar Uchu, which seems a variant of what Betanzos wrote. If his name is taken as Uchu, then it is the Quechua word for hot peppers.

Ayar Uchu was chosen to become a stone shrine on the top of the mountain Guanacaure, to which Inca youths went in order to be transformed into adults. As part of this, Uchu suddenly spread wings as if a condor and flew up into the sky to speak with the Sun, before returning and becoming stone so that he could stay there and be of service to his siblings and their descendants.

If we take this as an allegory of hot peppers, the story speaks of the transforming power of hot peppers, related to mountain peaks that rise into the sky, or condors that can fly high. It is not surprising that today, on top of the dish chiriuchu, the favored festive food of Cuzco tied to the continuation of the great Inti Raymi feast historically in its connection with Corpus Christi, slices of hot rocoto crown the mountain of food. The rocoto peppers often are both red and yellow, the sacred colors of the Incas.

These two Incas, Ayar Cachi and Ayar Uche, then, locate the story of the Incas in two condiments, one tied to the cave and the world within while the other is connected with a mountain peak and the sky. These are the two aggressively masculine condiments that make food tasty and which even today are commonly used to make food tasty.

Betanzos’ story of Inca origins connects the Incas with food, giving them a common origin with potatoes and corn, but a kin connection with salt and hot peppers, since they are the names of their ancestral brothers. As a result, it should not surprise us that this myth seems to still inform the food of contemporary Cuzco.