Two Stories, Two Suns, and Inca History

Inca history is like a pot smashed in time whose pieces are scattered. Scholars and others pick up the pieces, one at a time, and try to put them together to make the pot whole. But what once was an Inca masterpiece keeps coming out a sort of amphora or some other such Western object.

The great puzzle of this masterful society, stretched from present day Colombia to mid Chile keeps drawing in scholars with its wonders and its puzzles. As a result fine articles and books on the Incas keep appearing and our understanding grows.

Recently Dr. Isabel Yaya amplified our knowledge by reworking the pieces of the puzzle. In her book, The Two Faces of Inca History (Brill 2012), Yaya, who recently completed a Ph.D in history at the University of New South Wales and who is presently a fellow at the University of London’s School of Advanced Study, looked at the fragments of Inca past contained in the many colonial writings.

Written by a range of colonial and Church officials as well as scholars and others, these texts that themselves arrive in the present day in an often fragmented condition present images of Inca life that do not seem to fit together easily. While the field of scholarship has expanded with the discovery of new texts, it is also a difficult one of trying to find what goes with what and find glue that can hold them together.

Yaya argues that to find a glue we must look at the Inca through an Amerindian lens and realize that their notions of the past (i.e historiography) as well as of the organization of their society were not driven by the concerns of the Spanish world nor by the categories and single omniscient pretensions of contemporary life. Rather they were guided by two important aspects of Inca life: the movement of seasons from wet to dry and back again and the division of their city and state into two parts, or moieties, what is often called hanansaya and hurinsaya, or upper and lower halves.

While people who study the Incas have long mobilized the two halves and stated that dualism, that is the organization of life and the world into opposites, is an important part of the Inca puzzle, Yaya moves this further. She moves into the world of other South American societies to argue that these moieties are not like those found in other parts of the world. They do not need an overarching vision to ring them into a single society, but instead their endless separation and struggle with one another is enough of a whole.

This idea alone breaks much of classic Western thought, especially its fascination with overarching deity and nature, and allows Yaya to approach the historical fragments freshly. Yaya can ask how each of the authors relates to the Inca materials and what drives their accounts, at the same time she has a new glue and a new frame to compare them with one another and bring the fragments they contain together.

This is neither the time nor the place to get into the nitty gritty details of her argument that will keep her colleagues debating. Let us, instead, look at two key details of her book that anyone who goes to Cuzco will find interesting.

A contradictory set of stories tells the origins of the Incas. One narrates about a set of brothers and sisters who came out of the ground in Paqariqtambo, near Cuzco, and migrated to the Huatanay Valley while having adventures and building a cosmos. The other tells of a migration of the original Incas from Lake Titicaca and their settlement in Cuzco.

These stories are well known and, while some scholars try to synthesize them, many just leave them alone. Nevertheless, the idea of these two migrations has fascinated archeologists who look for evidence and disagree about how the stories might relate to what is found. (If you wish you can look at the work of Brian Bauer and Gordon McEwen. Their different books take different sides on these stories and their literal grounding).

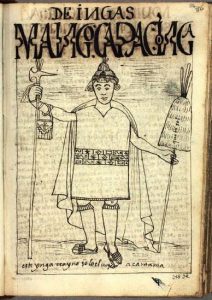

Yaya takes a very different approach. She establishes an argument that the two histories belong to different halves of Inca society. She holds the Paqariqtambo story of the Ayar brothers and sisters and their journey belongs to the lower half, that of hurinsaya, while the Titicaca story about Manco Capac (or Manco Sapaca as she calls him) belongs to hanansaya, the upper half.

Not only does Yaya see these stories as fueling different ritual lives for the two halves but also the political struggles and possibilities of different interest groups within the history that so complicate the colonial narrations.

Not only did the stories of origin differ between the two halves, Yaya argues they also engaged two different and competing sun gods who the Spanish worked to fuse into one. Yaya argues these two divinities with their ritual and political requirements imply different histories.

The older sun, related to the lower half, Yaya calls P’unchaw while the newer sun of the powerful upper half is Viracocha (Wiraqucha in her spelling). Just as the migrants from Titicaca came to Cuzco and dominated its inhabitants, according to the upper moiety’s telling, so their sun god also took over the weaker and older sun god that was already there.

Yaya argues that the Incas saw these two stories and two sets of realities changing in the course of the year. During the rainy season when clouds often hide the sun, Yaya argues it was the time of lower Cuzco and its god P’unchaw. When clouds disappear and the sky is clear Wiraqucha claims the day. But neither does so completely, sometimes during the rainy season the clouds would depart and a strong sun emerge while during the dry season sometimes it would rain. In this climatological reality, Yaya sees the organizing image of constant opposition and struggle that anthropologists have identified as being at the heart of Andean dualism.

The rains are still heavy in Cuzco though soon they will dry and tourism will become heavy again while the bright sun rules the sky. As these changes take place, Yaya’s book provides an important rethinking of how the Incas organized time and their empire.