Death in Mexico and Peru

As October runs down its days, the dead become more and more visible in ordinary life. In Peru, it is spring, the rains are beginning, flowers bloom, and the hills revive. North of the equator, it is fall, days are shorter, dark increasingly reigns.

I am reminded of an October when I was waiting to catch a bus in Salt Lake City and was talking to a high school student who waited at the same stop. Over the course of many days waiting we had established a speaking relationship. Out of the blue, he started talking to me about an important figure of Mexican folk devotion, La Santísima Muerte. She is known for her ruthlessness. He told me he was afraid of her because she grants your requests but then you owe her and if you do not follow through she will charge the debt to your children.

The official Catholic Church might reject her, but St. Death, as we can call her, is an important folk figure in Mexico and the subject of much writing. I was at a conference and heard anthropologist Andrew Chesnut discuss her. He was, at the time, publishing a book with Oxford University Press on her. Chesnut performed a quick comparison of Latin American understandings of death, such as the figure of San La Muerte in Argentina, and then came to Peru. He noted that the Andean core countries, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, seemed unusual to him because he could find no devotional figure that simply represented death, as was common in the rest of Latin America. In conversation, this led to an argument that death may be somewhat different in its experience and representation in the Andes.

In Mexico, Death is a Grim Reaper who comes for all and draws on Spanish traditions relating to death during the years of plague, even if she also draws on some indigenous roots.

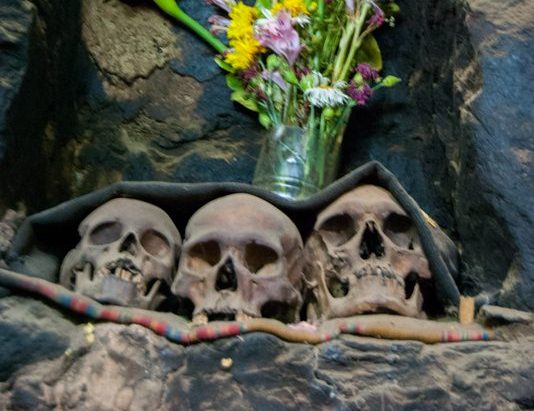

Like in Mexico, death comes for all in Perú. However, the folk traditions seem to focus much less on its coming than on how you socialize death, how you can guarantee an orderly transition of the soul of the deceased and how you continue for years (three at least) to maintain those passed on as part of your family and social network.

Folklore is filled with tales of the dead who are not completely dead, i.e. have not made the transition They are penando (suffering as well as paying for sins) and so still walk the earth, whether in the high mountains or in neighborhoods. There also is the problem of the Machus, the ancient dead who appear in society unless one is careful and aware. And, not far from the surface of the world, in caves for example, the Inca and other dead are often said to still live. Moments of contact, are dangerous, as is any contact that is not properly contained with the condenados, the condemned ones who are suffering, or with the Machus.

In a very short time, the streets of Cuzco will fill with bread babies which people will consume, as part of their celebration of the rituals of the beginning of November. Many will baptize them, manifesting in this way the concern with socialization.

Death is associated with rebirth and life, as a result. They also will first create a feast for the living, before feasting with their dead.

Death is not unchained in Peru and roaming the land. Those are the condenados and the machukuna, the dead who still participated in life, unchained from ritual and family.

This idea of difference cultures and approaches to death is intriguing and requires comparative research.