Christmas Carols in Cuzco

Jingle bells sounds from every speaker in this city where Pachacuteq once reigned. Christmas is here. Servers wear red caps with a white puff on top, and images of Santa Claus are everywhere, white beard, round belly and all.

People scurry to buy last minute gifts and to make sure they have bars of chocolate for the midnight cheer on the twenty fourth, along with tall boxes of panettones.

You look out at the heavy clouds, not snow clouds–no white Christmas here in the tropics, but rain clouds threatening a burst of wet chill and making buyers wait.

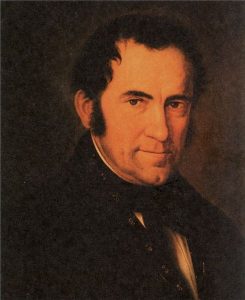

Silent night takes its turn in the play list. Its Spanish form is different than the one I learned on the US Mexican border when a child and it only shares a melody with the tune Franz Gruber wrote, as well as a sense in common with Joseph Mohr’s lyrics.

Given that the popular Christmas song comes from Austria and will soon celebrate its 200th anniversary, it would seem that this Christmas is universal, even though I see lining up on the street Indian children with fringed, colorful hats who speak Quechua.

Though it was not known at the time the Christmas hymn was first performed in Obendorf, the Austro Hungarian Empire, one of largest and most important political bodies in the world came to an end in 1918, just a couple of months before Silent Night had its first hundredth birthday. At the time of the song’s composition, Austria was one of the world’s great powers.

Even before then, the Same Hapsburgs who ruled in Austria had ruled in Spain. In fact, when the Spaniard Pizarro and his band took the great Inca hostage in Cajamarca, Peru in November of 1532, marking the end of the Inca Empire, one of the worlds largest, it was a Hapsburg who ruled in Spain.

The same powers that created and ruled the society in which Franz Gruber wrote the simple, yet peaceful melody for Stille Nacht, Silent Night, had earlier taken Peru from the Incas and thrust Christianity on them.

The Incas and their subjects response was mixed, of course, although an indigenous

Christianity soon sprang up. Many Incas embraced the image of the Christ Child as their own, reminiscent as he was of the image of the baby sun, one of the main images of the celestial orb that were celebrated in the Holy temple of the Sun in Cusco.

Since then, that image, the niño manuelito, or the Little Child Emmanuel, has become one of the most important images in Cusco and certainly one celebrated at Christmas, when he was ostensibly born.

All over the mountains and valleys near here stories of the playful image of the Christ Child abound, usually as a child rather than an infant. In Ccoa of nearby Chumbivillcas, the Church was supposedly founded on a place where two Christ children played with each other.

Another story explains the presence of the pilgrimage to Qoyllur Riti, a high glacier near today’s Cuzco. It is said that a Christ Child played regularly with a local shepherd boy and caused the families flocks to multiply.

If you go on You Tube, you can hear a very different kind of Christmas Carol from the Austrian Silent Night or the more modern Jingle Bells, one in Quechua sung by Children from the Mercedarian Youth Choir. It is called the Dear Starry-Eyed Child, Ch’aska Ñawi Niñucha.

Following the conquest, art that drew both on local thoughts and Christianity flourished in the Andes. From this sprang not only the images of the Niño Manuel that are found in almost every household in Cuzco and beyond (in fact they are important gifts to take from Cuzco to people around the world) song also bloomed. The local traditional of Christmas songs is called Villancicos.

Some thirty years ago, when Quechua and Spanish lived side by side in the minds and tongues of Cuzco’s elite, before the recent shift to only Spanish, you just about only heard these villancicos in the Andes.

Now with the increasing commercial integration into the Anglo American commercial and political empire, jingle bells and Gruber and Mohr’s silent night, along with every other mass produced Christmas song claims place in Cuzco.

Though, for a while following the Hapsburg conquest of Peru, it was joined with the imperial forces that also rocked Austria, a distinctive regional culture grew up that had both Inca and Christian roots. Now that is diminishing in the face of a unified commercial empire, once again, and jingle bells reigns around much of the world, along with Rudolph.