Archaeology, People, and Tensions in Cuzco

You may see the glories of Cuzco, the gigantic zig zag wall of Sacsayhuaman, the rounded blackness of the Qoricancha, or the shadowed masses of Hatunrumiyoq Street. From here opened an amazing empire. But that was centuries ago. The images of the past and its glories live today in a world of conflict and tension.

While the fight over statue of the Inca in the Plaza de Armas continues, many other struggles either sink into the background or spring into the open.

The new J.W. Marriott Hotel is an example. Built as a renovation and a new structure in Cuzco’s historical core, it has been controversial from the beginning. While there is little doubt about its majesty and quality, the concern was with the permits allowing for major excavation for a modern building (even if the facade and portions are authentically colonial) on what was a very ancient site of importance in imperial Cuzco.

All kinds of rumors surfaced concerning impropriety in the handling of ancient remains and the treatment of the ancient site.

But the Marriott is not the first example of these controversies. The Novotel, less than a block away, was also cited in the popular tongue as an example of impropriety in permitting and construction. Many argued it ruined an Inca wall and structure, though the result is an impressive hotel.

Recently, an anthropologist from Cuzco, Daniel Guevara, published an article about some different but related contradictions and tensions in the protection of cultural patrimony.

He mentioned that a dominant idea in Cuzco is that the city’s economy is based on tourists and, as a consequence, people such as those who visit the Novotel and the Marriott should have good treatment and priority over the local people of Cuzco.

While a very uncomfortable idea, I certainly have seen instances of this and felt its power in the city, all the while it troubles my egalitarian sense.

Guevara further talks about the notion that people such as the much respected Jorge Flores Ochoa, among others, have called Incanism in their studies of contemporary Cuzco. This idea holds that Cuzco is the modern inheritor of the Incas and that, as a result, its Inca heritage should be a source of local pride and a guide to the social and economic resurgence of Cuzco in modern Peru.

Incanism is a marketing strategy, Guevara continues, to create in the city an exotic sense of otherness and the living past that can draw people to come and visit. It also ignores the complexity of the contemporary city with its drama and differences of social class and ethnicity.

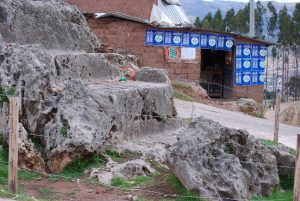

Guevara’s thought gets it oomph from the forced destruction of ninety homes, many of them two story, well established homes, September 27, 2012 in Cuzco where on 4.5 acres some 300 persons lived and had for around fifteen years.

Called “APV-La Fortaleza”, which ironically means “The Fortress” Neighborhood Association, it had been an invasion by a group of poorer settlers who had been looking for a place on which they could build homes. However, they chose to invade and build on land that was declared a protected archeological zone in the Wimpillay Sector, of suburban Santiago.

After years of conflicts and court cases, Cuzco’s officials moved to demolish their homes. Of course they resisted with sticks and stones. Some thirty people were arrested and an unspecified number were wounded.

You can imagine the anguish of these people who with their sweat had invested hope in homes that had built and lived in for fifteen years to see them destroyed to protect archeological sites.

Invasions, such as the La Fortaleza one, have been very common in Latin American cities, including Lima. They have been one of the main ways in which poor people have obtained homes. Although initially the homes are spare, many times not more than a box made of mats, over time people throw their heart and dreams of progress into them and build homes and neighborhoods.

The people who live in neighborhoods that are former invasions often are much closer to one another and show far more solidarity, community organization, and pride, than formally developed zones.

But the people of La Fortaleza locked horns, not with a local landlord, but with the powerful National Institute of Culture and the ideas that justify it.

Struggles pitting ordinary Peruvians agains archeology and the Culture Industry of Peru are not rare. From the perspective of archeologists many important sites are disappearing beneath settlements that appear like mushrooms after a rainstorm. Once destroyed a site, whether occupied by a fine hotel or a set of adobe homes, is gone for ever. Knowledge can no longer be gained from it.

Conflicts, like La Fortaleza, take place throughout Peru, especially in the capital of Lima where even high rise buildings abut sites with pyramids. There are more in the offing in Cuzco.

Guevara finishes his argument by calling for institutional means of avoiding these conflicts. Such means must include, he notes, a concern for the legitimate needs of Peru’s poorer people to acquire homes and make their dreams real.

Otherwise, he says, the weakest link in the chain will continue to be the site where Cuzco’s society will break.